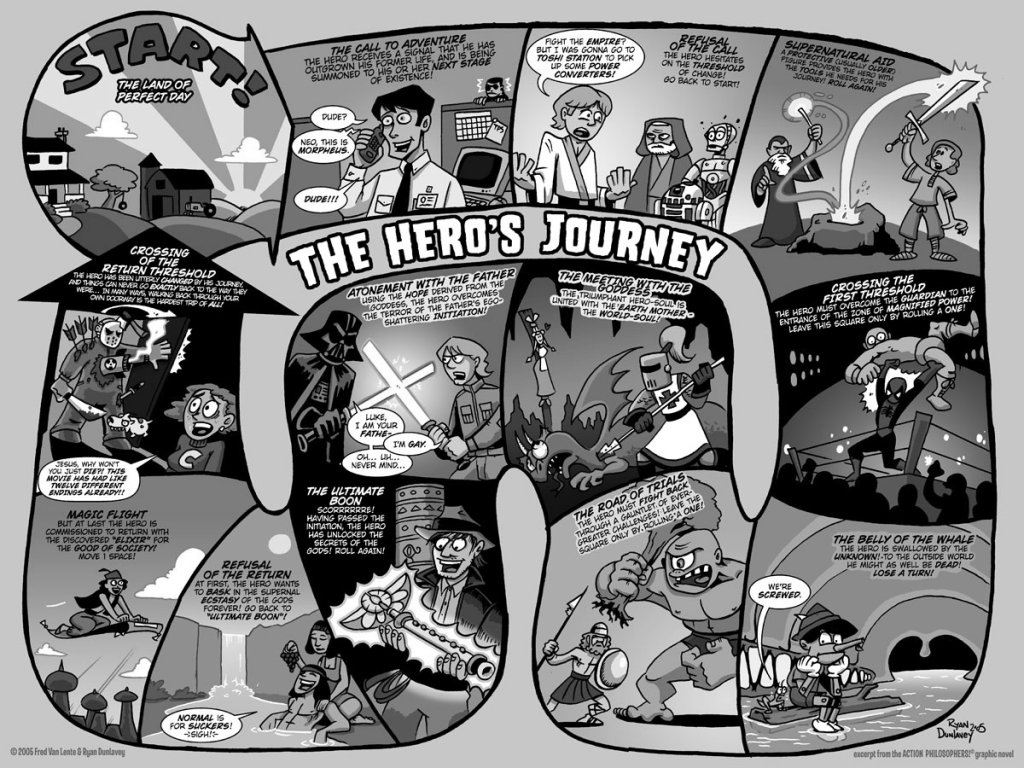

Hero’s Journey image above excerpted from Action Philosophers! © Ryan Dunlavey and Fred Van Lente.

All storytelling has inherent structures. But for the most part, communicators and creators employ just one. It really is time to move beyond the Hero’s Journey. Here are four alternatives to get you in the mood.

[DOWNLOAD this post for your leisurely viewing pleasure here]

Roland Barthes, master linguist and semiotician once said: “There are countless forms of narrative in the world.” And yet the majority of western storytellers have been ploughing just one narrative framework for over 60 years: Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey from the Hero with a Thousand Faces.

While it has its value, Campbell’s framework is, I would argue, no longer a useful model for narrative design on a structural level. Down below, I offer four alternative narrative structures that we could use to design intelligent stories more fitting to our contemporary context. But why the big deal about structure?

Structure makes the digital world go round

From data models and information architectures to the taxonomies and ontologies used in content strategy, clearly defined structures allow our stories to be read, understood, delivered, discovered and managed by our digital plumbing.

In fact, structured content is fast becoming a necessity, not a luxury. That’s why content strategists are already exploring intelligent content:

“Content that is structurally rich and semantically categorised … and is therefore automatically discoverable, reusable, reconfigurable, and adaptable” — Ann Rockley and Charles Cooper, Managing Enterprise Content

I’m going to be posting more on that later. But for now I want to explore something new on the structure of storytelling on a macro level. This is something that’s not yet in the content strategy lexicon, or communications either. It has major impacts on both.

Plot versus Story: a working definition

The most important structural element in story design is the difference between plot and story. The debate is deep and complex. For now, and in line with my take on storylining, I will define these as:

- Plot is the ‘what and why’ things happen

- Story is ‘how’ those things are told

Check out Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Russian Folk Tale (1928) as to why this works on a structural level. I have highlighted the most important bits for a quick read.

Drawing on Propp’s masterwork of narratology; while the ‘how’ we tell stories varies greatly even within cultures, the ‘what and why’ (the plot) is the most stable, structural element you can consistently identify. Or, as Propp put it, the plot is the ‘simplest irreducible narrative element’.

Now, back to the Hero’s Journey and some myths.

Myth #1: There is one storytelling form to rule them all

For over 60 years, the storytellers’ go-to model has been Joseph Campbell’s monomyth: complete with Volger’s adaptation of the Hero’s Journey and the three act structure. However, there are very good arguments as to why the monomyth is actually a myth itself, a strong argument that the Hero’s Journey stages are not the elements that drive plot at all, and indisputable proof that the three act structure is a nonsense.

So why do we not employ non-linear storytelling structures from film theory and information science, where appropriate? How about funky ones in experimental literature? Gossip clearly has its own messy, open ended narrative form specific to the ‘medium’. And the great Kurt Vonnegut described 8 story shapes here.

This said, my single biggest issue with Campbell is the monomyth itself. Supposedly, this ‘Grand Unified Theory’ of storytelling allows us to design stories that will connect with anyone at all — from any culture, from any part of the world.

In my experience, that’s just not true.

Try telling a Russian a Japanese story, a Kenyan a Canadian one, a German a Saudi story. Do they all ‘click’ regardless? Do they really all have the same plot structure – the same ‘what and why’?

Myth #2: Story structures can cross borders

Cognitive linguists have already proven many times that stories are interpreted differently by different cultures. But what about the actual structure of stories?

For several years I worked as an expeditor (troubleshooter) in supply chains that spanned Europe, the Middle East and Asia, and more. And boy, was it hard work on a communications level.

Sometimes I sat around a table with five or six different nationalities and tried to broker a consensus. Over time, I learned I not only had to adapt the my storytelling to ensure everyone had the same interpretation, but also adjust the order and logic (the ‘what and why’) — according to the preferences of each nationality on the table.

Over time, I started to figure out how to recognise, and adapt to, those structural preferences. I have come to believe that every culture has their own unique structural storytelling and communication preferences. And I think it’s perfectly reasonable to assume that distinct narrative structures are embedded/manifest wherever people group and interact.

What if?

What if there were stable narrative structures inherent within cultures — on a geographic, business culture, organisational purpose or values level? And what if we could surface them?

Applying some best practice content strategy and UX-thinking, we could map these structures against data-points. Create hypotheses about the storytelling preferences of our audiences, test and adapt story design accordingly.

Potentially, this would allow us to generate more powerful, personal stories via intelligent agents, social simulations and even crack the complexity of personalisation, omni-channel, and trans-media communications.

Down below are sketches of four narrative models to consider.

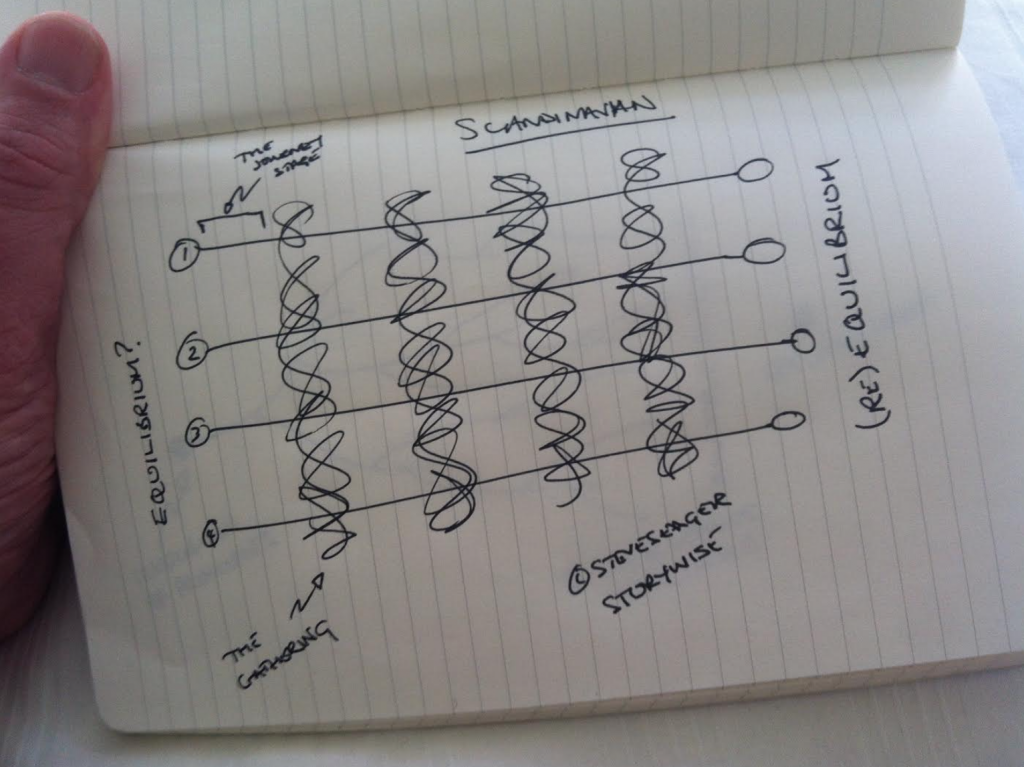

1. Scandinavian Narrative forms

Unlike Hollywood or Western European narratives which privilege a single protagonist (like Campbell’s Hero’s Journey), Scandinavian narrative forms are often built around multiple characters (most often three or four), with a ritual-based truth as the red thread. Yes, each of these characters has their own trajectory — a beginning, a sort of middle and a sort of end. And yet, during their journey, all the characters meet in a central meeting point several times. They discuss their adventure to date. Realign around the ritual truth. They fight. Learn. Develop — sometimes not. And then they move on to the next stage of their journey. There are typically five acts for each protagonist and, in line with the number of protagonists, there are usually at least three consequent ‘endings’, as well as a revisited collective adaptation.

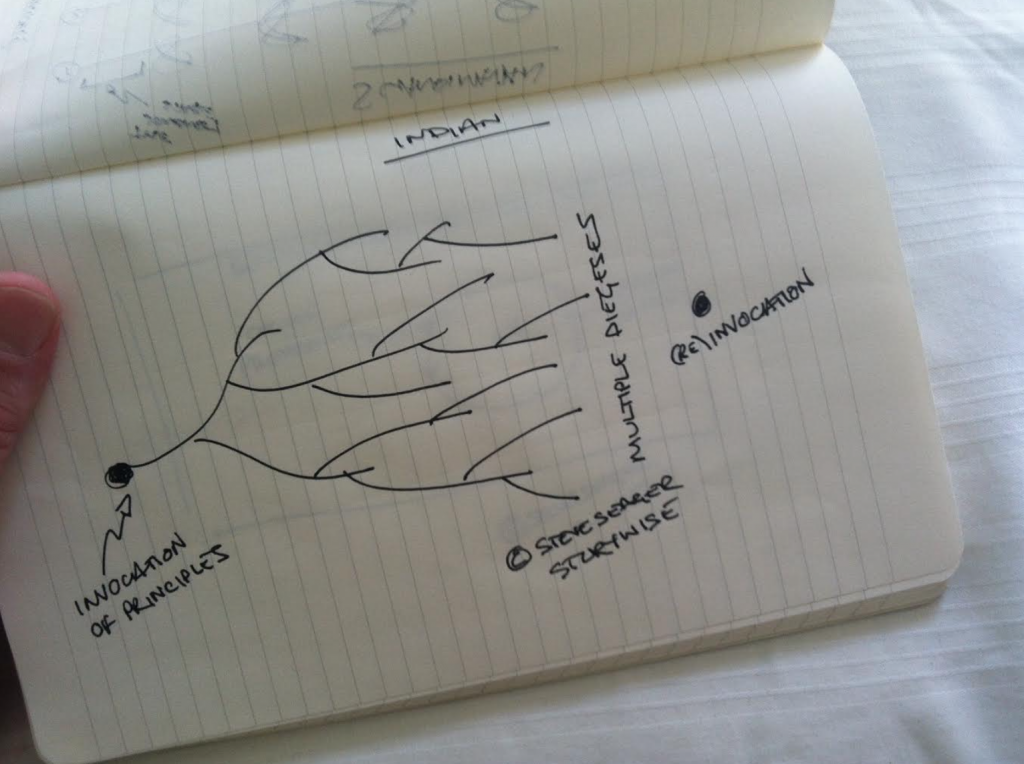

2. Indian narrative forms

Indian narrative forms are radically different from Western forms. Watch a Bollywood movie. One moment the film is a romance, then a thriller, then a musical, then a martial arts movie — confusing for a western audience but totally natural for an Indian audience. And this is just genre. As experienced in mathematics, microtonal music, literary forms and more, Indian culture seems to me, eminently comfortable with complexity, non-linearity and the non-binary nature of being. The traditional starting point of common narrative forms (especially in Hindi) is a religious/spiritual ritual invocation that establishes an emotive, spiritual sensibility for what follows. The ensuing narrative is most often dendritic in nature, and offers multiple diegeses (world views) exploring that original invocation, designed to accommodate many differing perspectives and world-views. ‘Closure’ is a re-invocation or adaptation of the opening invocation. And so the ‘end’ is a new beginning.

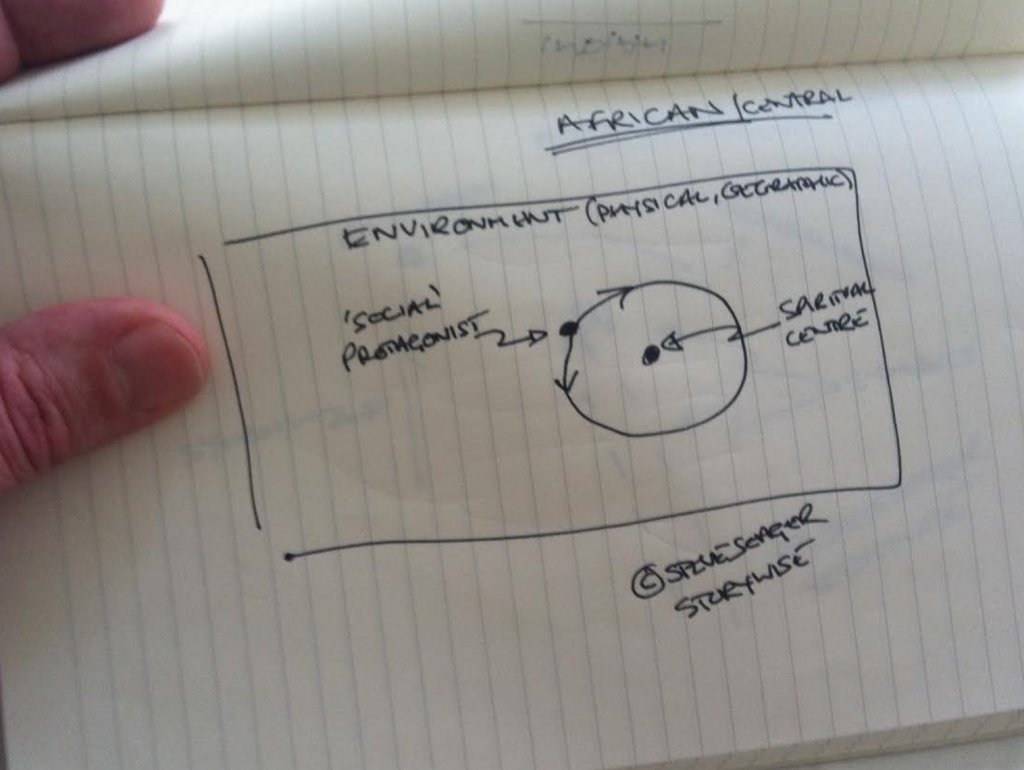

3. West African narrative forms

Unlike Scandinavian and Indian narrative forms, the stable plot elements in West African forms are often not function-based, but rather thematic and relational-based. Unlike many other narrative forms, the environment (the context) is privileged greatly over the protagonist. The social context is privileged over the individual protagonist, and the spiritual centre is privileged over the individual. All of the action — the ‘journey’ if you will — happens concretely within these clearly defined parameters. You can find this narrative model within many West African oral traditions, autochthonous film traditions, literature and more. And the storytelling too, privileges context, as the compositional framing remains static, while the characters enter and exit. Unlike Western filmic forms, this static framing is not a result of the theatre tradition, but of a temporal relationship between humankind and story, in which land defines the pace of events, not human activity.

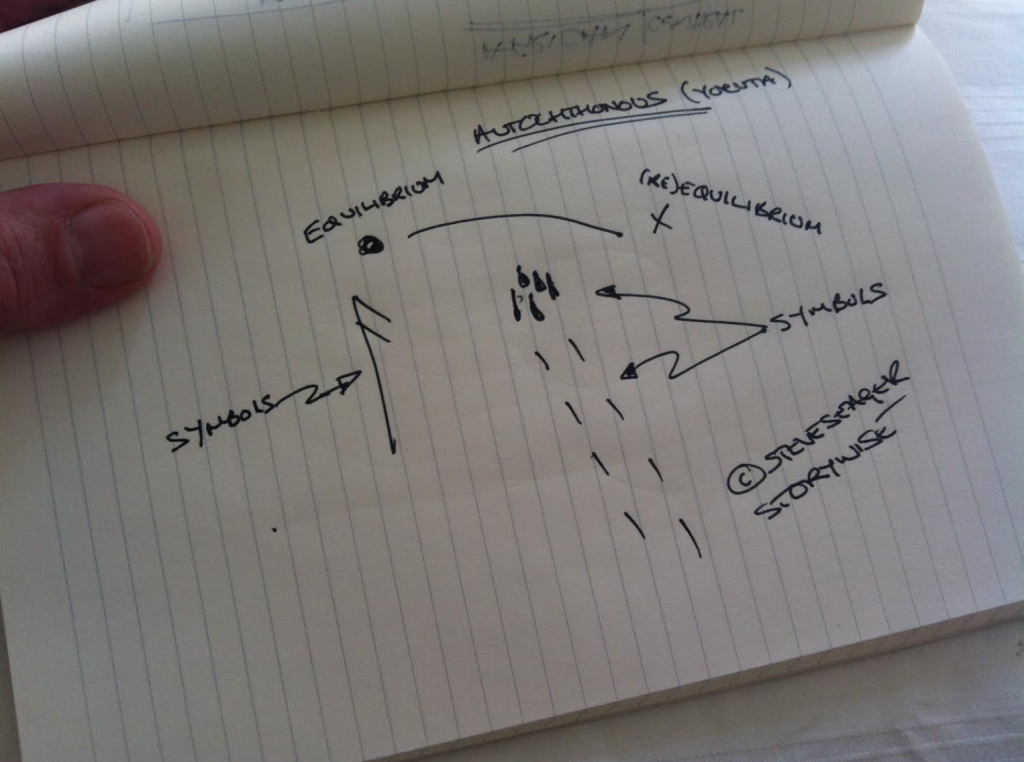

4. Autochthonous narrative forms

Autochthonous people are those native to the place they live rather than ‘just’ being born or engendered to the place they live. While my research is admittedly limited, regardless of geographical location, it appears to me that common autochthonous narrative forms are quite unlike any other forms — with the possible exception of avant-garde film. To illustrate: whereas many Hollywood films are all story and no plot (big visual plays for attention with little motivation) these narratives are, in effect, all plot and no story. While the plot points are offered, the actual interpretation of the ‘story’ is left entirely up to the reader. The prime narrative function; to equip the reader with the skills to ‘read’ and interpret signs and create their own stories. The key message is left entirely up to the reader to decide. These narrative forms are less didactic, and more interactive, learning device with no ‘auteur’ — only, in effect, an audience.

Applying these forms

When discussing editorial strategy with clients, I sometimes show them my models as an ice-breaker. I ask them to visualise the structure behind their organisational storytelling and choose a narrative model they think best fits with their culture. My goal: to see if I can surface the implicit narrative form.

Interestingly …

- Teams in strongly innovation-focused companies almost always choose the Indian narrative form.

- Teams in heavily campaign and product-focused companies almost always choose the Scandinavian model.

- NGOs almost always choose the Central African narrative model.

I am not yet 100% sure what this means. Are these narrative forms really fixed? At what level of culture? Do they adapt over time? Can they be engineered?

What I do know is that we live a data-driven world. And it is possible to map data against against narratological patterns. (See The Infinite Adventure Machine which uses Proppian structural analysis to automagically generate stories)

My belief is that if we focused on surfacing and mapping culturally-specific narrative forms as my sketches above, we could open up a whole new world of new insights into the storytelling preferences of our audiences — and so begin to design truly ‘intelligent’ stories.

— Steve

DOWNLOAD this post as a pdf here

These models have been in my head for years. It feels good to share them. Thanks to Kenneth Mikkelsen for the prod to share them as they are. And to my patient and smart other half, who helped me unpack them, then put them back together again. Many times.